Note: I was on vacation last week, at the beach with no internet access. It was nice. I still had XM Radio, though, and the FM transmitter on the MyFi is a godsend, allowing me to listen to ballgames in the house even though the only reception was outside on the front porch. Rather than blog, I read Jim Bouton's "Ball Four". Here is a review, of sorts, and some observations about the book."

Ball Four" was recommended to me by Rocket of

Nasty Nats, who described it as a "fantastic f**king read". As a review, anything beyond those three words is superfluous -- I kept thinking the same thing throughout my enjoyable trip through this book.

I was aware of Bouton and the book, of course, but I had never gotten round to reading it. For those who are not aware, it is Bouton's contemporaneous observations from his year with the expansion

Seattle Pilots in 1969, trying to make it in their bullpen as a knuckleballer after the fastball that helped him win World Series with the Yankees in the early 60s has deserted him. The book reminded me that I actually first heard of it in 1976 while watching the doomed CBS sitcom of the same name as an intrigued, baseball-crazed 8-year-old. My dad explained that Bouton was a funny guy who got into trouble with the things he said. My dad also liked Lenny Bruce, and I can now make the connection.

The book garnered headlines and controversy in 1970 because it broke the unwritten rule that what happens in the clubhouse stays in the clubhouse, and exposed ballplayers, general and specific (even famous specific, like Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford) for what they were and presumably still are: young men engaged in a competitive, high-stress profession who like to relieve the stress and tedium of their work with sex, drugs, booze, sarcasm and hijinks. One would find similar, if not identical, situations among Wall Street bond traders, a freshman class in a military academy, police squads and the like. No surprises there, really, especially 35 years later, but probably even in 1970, though many did not like to admit it.

While those vignettes are great fun and keep the book moving along, it is the more serious observations by Bouton of his profession that make the book the fantastic read. One in particular stood out -- his reaction to being sent down to the minors in mid-April, despite the feeling that he still could be a good pitcher:

I could be kidding myself. Maybe I'm so close to the situation that I can't make an objective judgment of whatever ability I have left. Maybe I just think I can do it. Maybe everybody who doesn't make it and who gets shunted to the minors feels exactly the way I do. Maybe too, the great cross of man is to repeat the mistakes of all men.

Here he has captured remarkably well the great mystery of success and failure, applicable not just to be baseball but any endeavor where one tries to take the measure of his/her talent and prospects for success. Is it luck or skill? Why not me? Look at him, I'm better than him, yet he has more success? Why? If I have succeeded before, was I just lucky? (As an aside, economist

Steve Levitt has insightfully observed that "almost every successful person underestimates the contribution of luck to their success.")

This book helped crystallize many thoughts I had been having from my following the Nats so closely this year, much more closely than I ever have any other team. This year has made me greatly appreciate the plight of the individual player who plays the game of baseball. If you read

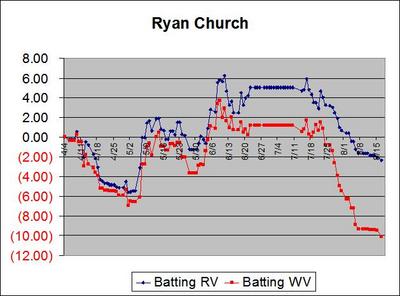

Ball Four, think of guys like Ryan Church, or Brendan Harris, or Jon Rauch, or Jeffrey Hammonds, or Wil Cordero, or Cristian Guzman, or Zack Day, or Marlon Byrd. They are all there, in some form or another. As fans of the team, we tend to view players only in relation to how they help the team win or lose -- once they are out of that picture, via a trade or injury or retirement, they quickly recede from our attention.

Ball Four forces them back into our field of view. It would have been great to be able to hire Bouton to spend this summer in the left field bullpen at RFK, keeping notes and a diary.

Speaking of which, about halfway through the book, it struck me how familiar Bouton's style was -- short, punchy sentences and half-sentences, organized by date, timed for the punch line perfectly, like you're sitting on the bullpen bench with him. Then I realized what was so user-friendly about it: Bouton was blogging, 30 years before blogs. Though it was edited and packaged for publication, the book could have just as easily been a series of blog posts during the season. For example, this little bit reminded me of the type of hilarious nonsense you might find on a blog thread or, more likely, in a

Yuda game chat:

An outfield game is making up singer-and-actor baseball teams purely on the sound of their names. Example -- Panamanian. Good speed, great arm, tempermental: shortstop Jose Greco. Or big, hard-hitting first baseman; strong, silent type: Vaughn Monroe. And centerfielder, showboat, spends all his money on cars, big ladies man, flashy dresser, drives in 75 runs a year, none of them in the clutch: Duke Ellington. Finally -- great pitcher, twenty-game winner five years in a row, class guy, friendly writers and fans alike. Stuff is good, not overpowering, but he's smart, has great control and curve ball, moves the ball around: Nat King Cole.

If you think this is a silly game, you haven't stood around in the outfield much.

Updating this for the modern recording artist -- clever, right-handed pitcher, intelligent, not a flamethrower, but several good pitches that he'll throw at any time, studies hitters, gets ahead, good fielder, dependable 20-game winner: Dave Matthews. Light-hitting utility infielder, small, over-acheiver, solid but unspectacular fielder, good contact hitter, good bunter and hit and run guy, rarely strikes out, works a walk often: Eddie Vetter. Goofy, left-fielder, wild, unorthodox swing, but makes contact a lot, with power, no batting gloves, just spit and dirt, uniform unkempt, colorful quotes to the media: Billy Corigan.

Bouton's blogging style provides an interesting take on the question of whether a modern-day "Ball Four" could be written about today's game. Indeed, could a player blog a

Ball Four today? I don't think so, for several reasons. First, it's hard work. Bouton needed over year and an editor to produce Ball Four, and spent a lot of his time on it in season. He was a veteran pitcher who could afford the time not spent on trying to develop his skills and make a name for himself. Second, if the player did blog, it would quickly be noticed, and any controversial thing he said would be seized upon by the media, fans and others with an insatiable appetite for news about their team. This would likely not be very popular with management and other players, just as Bouton's book was slammed, only in a blog it would be real-time, and not in the offseason. Third, I think the amount of money players make these days relieves some of the tension that keeps Bouton's book together, namely the real concern players in 1969 had about their financial situation if they were cut from the team. I don't think there is enough of that tension in a major league clubhouse these days -- maybe on a minor league team, but not in the big leagues. Fourth, I think Bouton is a rare combination, someone with the ability to perform well in two areas that are usually mutually incompatible: sensitive, intelligent observation and big-time professional sports. It is my view that the fishbowl in which most athletes live nowadays,

from a very young age, tends to diminish whatever reflective ability they might have had, because such introspection is probably death to the ego necessary to succeed in the current environment. Bouton describes it this way:

I've had some thoughts on what separate a professional athlete from other mortals. In a tight situation the amateur says, "I've failed in this situation many times. I'll probably do so again." In a tight situation the professional says (and means it), "I've failed in this situation and I've succeeded. Since each situation is a separate test of my abilities, there's no reason why I shouldn't succeed this time.

Then there is the case of the professional player who is not professional enough. He goes on a fifteen-game hitting streak and says, "Nobody can keep this up." And as the streak progresses his belief in his ability to keep it alive decreases to the point where it's almost impossible for him to get a hit.

The real professional -- and by that I suppose I mean the exceptional professional -- can convince himself that each time at bat is an individual performance and that there is no reason he can't go on hitting forever.

Is that clear? If it is, perhaps you ought to check with your doctor.

Finally, the last reason I think we won't see another Ball Four is that we don't really need one. Bouton's observations are timeless, and it would be difficult for the 2005 author to add to what he has so concisely captured in his book. Only the names and some of the specific hijinks would change, and some of those might even be more bland. Readers can use their own imaginations and knowledge about their teams and come up with their own Ball Four for their favorite club.